Bitcoin and Anonymous Transactions

Note: I do not endorse use of Bitcoin for any illegal activities. Like many, I regret the neccessary tradeoff between freedom, privacy and legitimate legal enforcement.

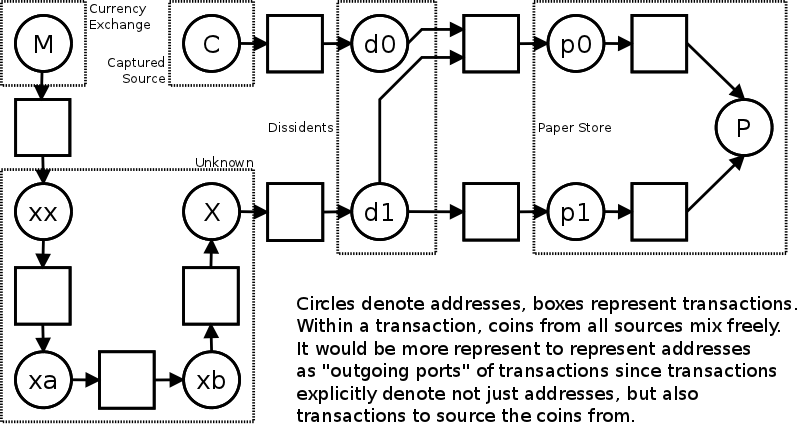

One of the much touted advantages of Bitcoin is its anonymity. The full record of all transactions is by the very nature of Bitcoin completely public. However, transactions move coins between a set of incoming addresses and a set of outgoing addresses, and the addresses are not tied to any particular entity; an address may belong to anyone and Bitcoin includes no way to tell.

The problem, of course, is that there might be ways to tell outside of Bitcoin, especially if you are legal authority (or good at finding security holes; or a Google user). Let’s say someone gives a donation (from address X) to an illegal free speech organization in Burma, and you want to figure out if it was a Burmese resident – and his address, in that case. The organization uses anonymous donation-specific addresses dnum. It wants to purchase a stock of paper for leaflets delivered to a conspirational address, without tipping off the secret police.

Let’s assume the secret police captured a computer of another supporter of dissidents. They retrieved the source address used for donations (address C) and now they look at where the coins went. A complicated bead net of addresses that merge and split coins among each other unrolls. The trouble is if it is possible to identify some of the addresses in the net. By government order, all incoming payments to the paper store are transferred from order-specific address p? to a single police-registered address P. The first order was paid at address p0, the second would be paid at p1.

The police can now clearly see the coins from address C, transferred to donation address d0, have been used to pay for paper and they will inquire in the store about customer of the address p0. But they can also see that other money have been used for this purchase as well. The trail goes through addresses X, xb, xa, xx, all unknown to police, but arrives to xx from M, the main coin store address of the local Bitcoin exchange. The authorities inquire at the exchange and get bank account number associated with the outgoing payment. The bank happily provides the address and the police is on its way. Does the bank account owner also own the address xx? And what about xa, xb and X, are these her addresses (used for keeping order in the books or to muddle the tracks) or someone else’s? Whose and why did the money go there? The case is not proven yet, but a person is already questioned at the secret police office and in a totalitarian regime, the burden of proof is effectively on her. The paper paid for at p1 will never arrive, but several black cars will.

(The xx-xa-xb-X split can be improved by sending parts of the amount to different addresses, then sending coins between them, and so on, but AFAIK this does not really help anything much as the coins are still being passed within a closed subgraph. Also, the dissident organization might try to avoid mixing independent sources in payments, but this may be difficult if you live from small donations.)

So, all is lost and hopeless, back to good old cash? Well, not necessarily. There are various approaches to combat the problem.

Solve part of it outside the box. Launder coins abroad. Spend them on legitimate-looking puppet causes while staying sure they either return to you or get sent the right way. Repeat and rinse several times. Preferably include real people with googleable Bitcoin addresses early in this chain to completely dissociate yourself from the coins in the public record. Of course, you need some real-world cooperation and friends worldwide. Similar approaches like dissociation by re-selling goods may be considered, but they seem very cumbersome, error-prone and likely losing money (or needing large investments and much time). This all could become a lot easier when paying with bitcoins in person becomes commonplace.

An obvious scheme to muddle the tracks is a mixin service (an escrow service might do this as a side-effect). Many people send in coins, they are all included in a single transaction and this transaction has many outgoing addresses for each user sending in money. It will split large pile of possibly suspect money to many small piles that can be used separately, and in the transaction it will be completely unclear which of the many source addresses is the source of the coins. Repeat few times with different sets of co-mixers and you have pretty much perfectly fogged the origins of the money.

It sounds great but it is fraught with many practical issues. Most obviously, you need to trust the service with your money; you send it in, it might arrive back or maybe not (they are scammers, or maybe just have technical trouble or got hacked). It should definitely be set up in some “safe” country. And still, you need to trust it is not logging anything, nor is its ISP, and nor is your country’s Great Firewall (i.e., use tor). Your government in fact secretly running this service would be a masterstroke. And of course, you absolutely need the “many people” part as well, so that you are actually mixing the coins with others. But these “many people” should be mainly honest persons with legal coin targets, there is not that much point in mixing if you are mixing just with crooks. For the same reason, “many honest people” will be reluctant to get into the trouble needlessly and mix with the crooks and you. An escrow service with mixing as a side-effect could alleviate this issue somewhat.

But what about a more elegant way? When making a transaction, you can pay a transaction fee, mainly to ensure speedier inclusion in a block. The transaction fee goes to whoever mines the block that includes the transaction. There is no upper bound to a transaction fee. We will spill coins in the fees.

The idea is similar to a mixin service; but instead of requiring voluntary participation, we use the txfees and the whole block chain as a mixin platform. In exchange, we concede that we cannot have all the money, but only some large fraction (a third? a half?). We will produce dummy transactions that move all the coins to the txfee, then collect part of it back in block generation payouts. This is completely legitimate and automatic; blocks generated by us and by other solo miners (pools are easily identifiable) are indistinguishable. Some of the money will return as clean laundry while the rest goes to support the Bitcoin system.

The practical implementation is simple. First, one needs to choose the ratio. The smaller the ratio, the harder to track the most common destination of the spillage, but the less money you get, obviously. Then, you create many small fee-spilling transactions transactions. (More means better laundered for further use, but take more time to get.) You keep part of them for your own blocks and broadcast the rest for other miners to pick up. You can get very smart about this, scanning the p2p network to broadcast to solo miners preferentially (you will be better masked), do some probabilistic modeling on the blocks you create, and so on. The big catch is being able to produce blocks at sufficient pace. The answer is either making a huge investment and building a massive solo rig, or just renting one! There are good rigs for rent. It is again important to rent abroad and make sure you cover your tracks well when paying rent. Of course, this is more practical for the accepting organization than the individual donator.

This proposal is far from perfect, but it should work and I have not seen it mentioned yet. My main point is that there may be more tricks like this and the anonymity discussion might yet get interesting.

Recent Comments